Bringing the Mason Community Together: Patriot Center, the Center for the Arts, and the Bellarmine Chapel

During President George W. Johnson’s tenure at George Mason, construction was commonplace; new dormitories and academic buildings sprouted all over campus. Residence halls and classroom space resulted from the practical needs of the student body, but Dr. Johnson desired George Mason serve not only its students, faculty, and staff, but also the Fairfax and Northern Virginia communities as well. Three special buildings have left their unique mark on the campus and continue to shape its legacy today.

The Patriot Center

The white “dome” of Patriot Center is an instantly recognizable feature on George Mason’s campus. The 10,000-seat arena, which hosts sporting events, concerts, and other major performances, has served the campus since its completion in 1985. [1] Construction began in August of 1983 but was continually hampered by a series of unfortunate events. Bad weather contributed, as did an accident with a crane that collapsed onto the roof, damaging several large beams but harming no workers. [2] Contractors also discovered during the process that the composition of the soil would not support the load of the planned concrete columns, so drawings had to be revised after the columns failed inspection. [3] Finally, the theft of $12,000 worth of tools and heavy equipment, though no building materials, added to the delays. [4]

There was some tension regarding Patriot Center’s completion date, which was continually changing due to unforeseen occurrences. Chris Allen, the project manager for the Gilbane Building Company, expected the Patriot Center to be ready in January 1985 after the target projection date of November 1984 was no longer possible. [5] When January came and went, President Johnson expressed —with typical forwardness—his determination to see the finished product sooner rather than later: “We will have graduation in the arena on May 18. You may have to wear a hard hat, but we’re having it in there.” [6]

President Johnson got his wish. Though the building was not completed by May 18 and students had initially been told that their graduation would be held on the Quad in front of Fenwick Library, the university received special permission from the contractor to use Patriot Center—which had passed the necessary inspections—for the ceremony. [7] The $16.7 million complex opened officially on September 12, 1985. [8] Basketball coach Joe Harrington believed that the new center would bolster recruitment efforts and called Dr. Johnson “a president who is not only a dreamer but a doer.” [9]

George Mason became the first university ever to contract a private firm to manage its arena, as opposed to hiring a professional staff member to take charge of the Patriot Center. [10] Centre Management, which scheduled many events in the greater Washington, D.C. and Baltimore areas, was chosen in 1985. The company worked closely with the university to ensure that their policies were in accordance with George Mason’s guidelines; for example, shows were only scheduled on weekends or when school was not in session, often at the expense of a profit, because of parking shortages that inconvenienced students. [11] The arena established itself as an attractive venue for shows too small for the 19,000-seat Capital Centre in Largo, Maryland (also run by Centre Management), but too large for concert halls like DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. Despite the publicity, Patriot Center did not see great returns during its early years of existence. In 1986, its 80 events grossed $2.6 million. [12] Centre Management predicted the 105 shows slated for 1990 would gross about $3.8 million. [13] While Centre Management only made an estimated $75,000 a year according to Mason officials, the management company claimed it had helped Patriot Center gross over $13.5 million in its first four years. [14] It credited this revenue to its suggestion that George Mason bring major performers like Kenny Rogers, The Beach Boys, The Muppets, and the Harlem Globetrotters, among others, to the Center, rather than reserving it solely for sports. [15]

George Mason officials indicated that Patriot Center generated about $300,000 annually toward subsidized student activities as of 1990. [16] The student population—generally the target audience—was given preferential treatment. Students received discounts for events in Patriot Center, were admitted to all Mason sporting events for free, were able to suggest shows to Centre Management, and were offered employment and internship opportunities. [17]

The Patriot Center also aimed to serve the larger community; family shows like the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus and Disney on Ice continue to be extremely popular. This is the scenario that President Johnson envisioned, where George Mason’s presence in and links with the surrounding community are clearly evident. He called the completion of Patriot Center “a rite of passage for GMU…a coming of age.” [18]

On October 4, 1985, the arena was open to the public for its first event; a sold-out crowd, which included actor Jack Nicholson, watched an exhibition game between the New York Knicks and the Washington Bullets. [19] When asked which team he thought would win, George Johnson replied, “George Mason is going to win tonight…the future looks very good.” [20] He was right: now managed by Monumental Sports & Entertainment, the Patriot Center boasts a total attendance of more than 10.5 million for nearly four thousand events. [21] It hosted the Men’s Basketball CAA tournament in 1986, the Women’s Basketball CAA tournament in 2005, the NCAA Men’s Volleyball championships in 1990, and two of George Mason Basketball’s NIT appearances (in 2002 and 2004). In 2011, the trade publication Venues Today ranked Patriot Center eleventh nationwide and seventeenth worldwide in ticket sales for venues with a capacity of 10,001-15,000; likewise, that same year, the trade magazine Billboard ranked it eighth nationwide and twentieth worldwide for top-grossing venues that accommodate the same capacity. [22]

Update: On May 7, 2015, the university announced that the name would be changed on July 1, 2015 to "EagleBank Arena at George Mason University" following a partnership deal with EagleBank.

The Center for the Arts

While Patriot Center’s large venue is a great place to showcase athletic talent, Dr. George Johnson and his wife, Joanne—a former chair of the George Mason Fund for the Arts and a longtime patron of the performing arts--also sought an impressive setting in which to feature outstanding dancers, singers, musicians, and other performing artists. No such facility had existed for most of Johnson’s tenure. It was not until 1988 that funding for the proposed Performing Arts Center was granted by the state legislature. Performance revenue and student fees also contributed to the construction of the $10.6 million building. [23]

The completion of the Center for the Arts, initially called “Humanities III,” was the final component of a three-phase Humanities complex. The first phase --now known as the deLaski Performing Arts Building—was completed in January 1988 and includes music and dance studios, classrooms, a small recital hall, and the Black Box studio theater which seats one hundred fifty people. Humanities II consists of administrative offices and was completed in the fall of 1989. [24] The Center for the Arts serves as the “performance arm” of the entire complex, in part because neither the Black Box nor Harris Theater can accommodate a full-size symphony orchestra or large theater or dance troupes, but also because of its beauty and architectural innovations. The “crown jewel of the Center for the Arts,” the state-of-the-art Concert Hall, is a unique structure designed by theatrical and acoustical consultant George Izenour. [25] The famous engineer, inventor, and writer served as the lighting director and designer for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theater Project in Los Angeles in the late 1930s, established the Electro-Mechanical Laboratory at Yale University, and consulted on the design of over one hundred buildings around the world. [26] A large collection of Federal Theater Project materials is housed in the Special Collections Research Center within University Libraries.

The Concert Hall’s maximum capacity is two thousand, but the space can be reduced to just eight hundred seats when a performance is smaller or a more intimate setting is desired; acoustic panels can be adjusted to complement either situation. [27] The stage is also adaptable—in addition to the main stage, a front “lift” stage provides an enlarged space for actors when raised, an orchestra pit when lowered, and further seating if necessary (when portable rows of seats are raised to the stage level). [28]

The Grand Opening of the Center for the Arts on October 6, 1990, highlighted the Center’s exceptional Concert Hall. Marvin Hamlisch, the Oscar-winning composer and the evening’s Master of Ceremonies, noted: “There are a lot of wonderful performers here this evening, but the star is undoubtedly the theater.” [29] Although certainly a centerpiece, the Concert Hall was not the only component that impressed; the dazzling show featured celebrated performers including, among others, the comedy troupe PDQ Bach, opera singer Roberta Peters, the Fairfax Symphony Orchestra, and members of Broadway’s A Chorus Line. [30] Dr. Johnson expressed his excitement for its future: “What’s really happening here tonight is the beginning of a dream. Dreams are the stuff of this university. A university that conceives of itself not as a place, but as a state of always becoming, dreams realized and dreams begun.” [31] Johnson emphasized the importance of the bonds that the Center for the Arts had the potential to create between the university and the community; it allows “a blending of students and community so that we gain support from the community and we also enable our students—when they graduate—to have a community receptive to them.” [32] He added that the Center’s professional productions also “enable students to be more culturally literate and exposed to serious theater, dance, and orchestral music, visiting companies from abroad, and to be able to interact with those people.” [33] The opening of Humanities III provided “a hopeful predilection that GMU and the surrounding community will enjoy a long and fruitful relationship immersed in the arts… [that will bring] prestigious cultural riches to the campus and to northern Virginia.” [34] The Center for the Arts has done just that.

The Bellarmine Chapel

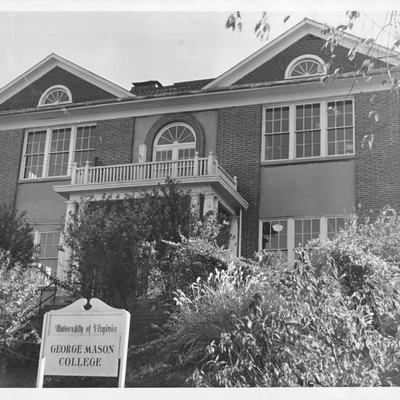

The Center for the Arts was not the only dream fighting to become reality in the early 1990s. Active student ministry programs have been involved at Mason since its inception, and as early as 1961 the University of Virginia planned for the eventual construction of a chapel at Fairfax, as had existed at Charlottesville. [35] Mason’s Catholic Campus Ministry (CCM), which serves a large student population at George Mason, was one such group that desired a chapel in which to hold services and social events. Students often gathered in a small house that served as rectory on Roberts Road (behind President’s Park), overtaking the first floor. The Reverend Robert Cilinski, who came to George Mason in 1986—the year that the Bishop of Arlington, John Keating, first assigned a full-time priest as chaplain of the campus—joked that “For eight and a half years, I was basically living above the store.” [36] Services were also held on-campus in Student Union Building I and Lecture Hall. The Diocese of Arlington purchased the property on Roberts Road, just off-campus, that housed the rectory to establish a Catholic Campus Center, but the fast-growing community outgrew the space quickly.

In 1992, the Diocese purchased the adjacent property, which had at one time belonged to the Kappa Sigma fraternity at Mason, to build a chapel. Interestingly, the property is very near the former St. George’s United Methodist Church, which is actually part of George Mason’s Fairfax campus and is located on Rockfish Creek Lane, just off of Shenandoah River Lane. The building was donated to the university and named George’s Hall. It was later renamed Carow Hall for the family who gave it to the university, and it now houses the Center for Study of Public Choice. [37] Construction began in August 1993 to create what Rev. Cilinski called “a modern version of a colonial chapel.” [38] Architects sought to reflect the style of buildings within the City of Fairfax as well as older churches in the area, like the historic St. Mary’s. The tract had a forty-foot slope which had to be built up so the front of the chapel would be level with Roberts Road. Rev. Cilinski reached out to people from all backgrounds: “We wanted to be a beacon. We wanted to be a ‘welcome to worship’ to the campus community.” [39]

Rev. Cilinski declared that the completion of the Chapel was the result of the students’ shared dream and made possible by the “generosity of the Northern Virginia Catholic community.” Funds were contributed by students and their parents, the Diocese of Arlington, and other local churches. [40] After much discussion, the chapel was named for St. Robert Bellarmine, a cardinal from Sienna, Italy, who lived from 1542 – 1621 and according to Rev. Cilinski was “known as a scholar, a defender of the faith, and a lover of the poor. He dedicated his life to working with youth.” [41] The name seems an apt choice for the chapel, which continues to serve the campus community today under the direction of its chaplain, Rev. Peter Nasetta. During the Friday of freshman move-in, the Chapel hosts a luau and pig roast that attracts well over a thousand new freshmen and provides a way for them to meet new people and learn about the community. It also offers a wide variety of service and community outreach programs.

A common thread links these three buildings: each was the result of a dream to serve and develop a close relationship with the larger community and to provide enriching cultural and social experiences for those associated with the University. George Johnson’s goal to expand George Mason’s influence beyond the boundaries of the university is reflected in part of the school’s mission statement: “To maintain an international reputation for superior education and public service that affirms its role as the intellectual and cultural nexus among Northern Virginia, the nation, and the world.” [42] It is a role George Mason will continue to strive for, and it will be achieved by recognizing itself, in Dr. Johnson’s words, as “a university that conceives of itself not as a place, but as a state of always becoming, dreams realized and dreams begun.” [43]

Browse items related to Patriot Center.

Browse items related to The Center for the Arts.

Browse items related to Robert Bellarmine Chapel