The Longest One-Year Appointment: Lorin A Thompson

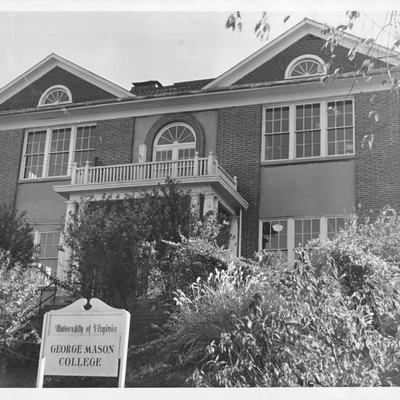

With the departure of Mason’s Director Robert H. Reid, University of Virginia President Edgar F. Shannon tapped Lorin A. Thompson for the post. A proven leader as Director of the Bureau of Population and Economic Research at Charlottesville and an expert in population demographics and education, he seemed the perfect fit. Already sixty-four years old and nearing retirement, he accepted what was to be just a one-year appointment under the new title of Chancellor of George Mason College, reporting directly to Shannon. Dr. Thompson can be considered among the “founding fathers” of George Mason University as his work - both outside the university and as its chief executive – has had lasting effects on its development. What began as a one-year appointment as Chancellor of a branch college became a seven-year run, which culminated in his appointment as President of the newest university in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Thompson moved to Virginia from the Midwest in 1940 to work for the Virginia State Planning Board in Richmond and direct the Virginia Population Study. In 1944 he went west to Charlottesville to head up the Bureau of Population and Economic Research at the University of Virginia. There he conducted statistical and economic research for state agencies and organizations. One such organization was the Virginia Advisory Legislative Committee (VALC), where, in 1955, Thompson contributed to a report entitled The Crisis in Higher Education in Virginia and a Solution. In this report VALC, bolstered by Thompson’s studies, argued that Virginia’s universities and colleges would not be able to accommodate its “Baby Boom” generation, and more higher-educational opportunities, in the form of branch colleges, were needed. [1] Less than one year later after the report was published, the Virginia General Assembly issued a resolution establishing a two-year branch college of the University of Virginia in Northern Virginia.

By the time Thompson arrived in June of 1966 enrollment had more than doubled (from 356 to about 840) in the first two years at Fairfax. The original master plan of 1960 allowed for a peak enrollment of only about 2,500 total. In his first public statement of June 6th, he addressed the future growth of the college, listing four action items needing to be in place for growth to happen at Mason – additional land, a comprehensive educational program, a new master site plan, and access to capital. At the end of this message, he hinted that it was his opportunity and responsibility to transform George Mason into an independent university. It was, as he characterized it: “time to move ahead boldly toward the development of an important university in the Northern Virginia area.” [2]

Keenly aware of the need for more land, Thompson hit the ground running. It was determined that the additional acreage surrounding the campus (nearly 450 acres in all) would cost $3,000,000 to acquire. He and his small staff prepared a slide show featuring some diagrams of new buildings that were needed for George Mason’s growth. Thompson took the traveling slide show to the people and elected officials of the local municipalities: Alexandria, Fairfax, Arlington, and Falls Church. Arguing that for the cost of a steak dinner ($4.50 at the time) for each resident in the region, Northern Virginia could have a top-flight university. [3] His persistence paid off, as local leaders and the people of the area agreed to fund Mason’s expansion. Through bond referenda and generous allocations by local governments, Thompson succeeded and raised the $3,000,000. The land was officially transferred to the college in July of 1969.

Thompson’s initial success must have impressed Virginia Governor Mills E. Godwin, Jr. who brought his Capital Outlay Budget Advisory Group to Northern Virginia for the first time in the state’s history to visit George Mason College in May 1967. Thompson suggested to the group that George Mason would need over $39,000,000 for the major expansion he envisioned over the next seven years. Included in this plan were the addition of a stack tower to Fenwick Library, a new arts and sciences building, student union, and a health and physical education building and gymnasium. [4]

Beginning in 1967 Mason took several internal steps toward becoming a viable independent institution. A number of key studies were done by and on behalf of the college, culminating with the 1970 Self Appraisal, which was required for accreditation. Each argued for an expansion of facilities, programs, services, and for the eventual independence of the college. Thompson believed that future enrollment would be much higher than his predecessors did, and these studies anticipated a student body of 10,000 to 15,000 by 1985. [5] Enrollment by 1970 had already grown to 2,390. [6]

Also, beginning in 1967, George Mason began to experience the first strains of social upheaval. Even though events at Mason were not as violent, destructive, or highly publicized as those at other colleges and universities; certain episodes during the late 1960s challenged the entire Mason community regarding free speech, academic freedom, and racism. The radicalization of the student body (albeit a very small percentage) with regard to the Vietnam War was illustrated in the student newspaper The Gunston Ledger, later renamed Broadside. Student participation in demonstrations drew a patient yet firm response from Thompson and the administration at Charlottesville. The long-running episode concerning faculty member James M. Shea’s classroom techniques and actions in opposition to the Vietnam War became a very public crisis at Mason until his exit in 1971. In that same year a report by the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, entitled George Mason College: For All the People?, examined the makeup of the student body and questioned whether or not Mason was trying hard enough to recruit minorities.

In the meantime, while all of this was occurring, Mason’s enrollment was soaring. It was approaching 4,000 in January 1972. When the former Fairfax High School on Route 29 had become available at that time, Thompson made a play to obtain it for George Mason. Striking a clever deal with the Fairfax County Public School System, Thompson, working with the George Mason College Foundation, bought the site. Renamed “North Campus,” the new building added 80,000 square feet of desperately needed space.

On Friday, April 7, 1972, Chancellor Thompson brought a small group of George Mason staff and students to meet with Virginia Governor, A. Linwood Holton, Jr., in Richmond. There, they participated in the Governor’s signing into law H-210 separating George Mason College from the University of Virginia and renaming it George Mason University, effective July 1, 1972. During the brief afternoon ceremony, Thompson and his colleagues proudly looked on as Holton signed one of the most critical documents in the history of the very young institution. A month later, during the first meeting of the new George Mason University Board of Visitors, the Rector, Fairfax Mayor Jack Wood and the Board, appointed Thompson President of George Mason University. Finally, on June 30, 1973, Dr. Thompson actually retired. He handed the reins over to Dr. Vergil Homer Dykstra in a brief ceremony in his former office. Completed in October 1971, the Arts and Sciences building was later renamed Thompson Hall in his honor.

Dr. Lorin A. Thompson will always be remembered as the president under whom George Mason took its first steps toward becoming a regional leader in higher education. During his seven-year tenure the size of the Fairfax campus went from 150 to nearly 600 acres. He initiated $10.5 million in construction projects, and ten different campus buildings were completed. He laid the critical economic groundwork for others who would follow him. Enrollment went from 840 to 4200. And perhaps most importantly, George Mason went from being a two-year branch of the University of Virginia to an independent university of its own.