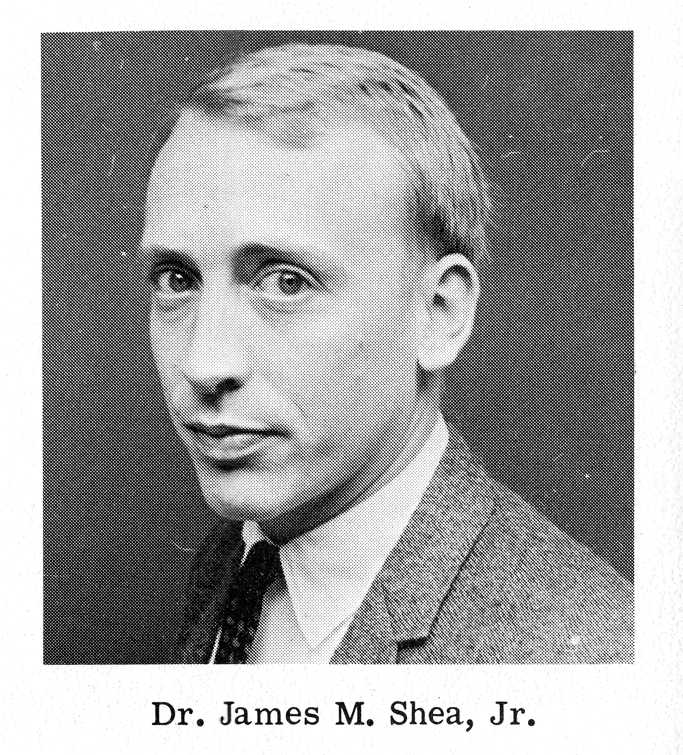

The Dr. James M. Shea Affair

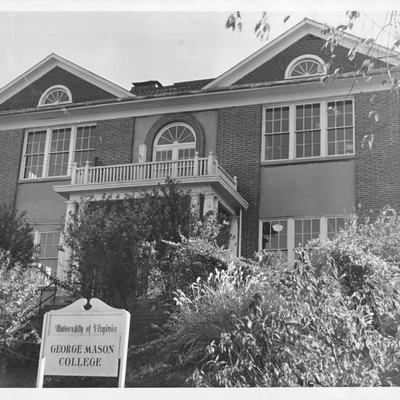

The James Shea episode was yet another difficult test for Mason to weather during its early development. In this case, the limits of the college’s support of academic freedom and freedom of conscience were tested by a member of its faculty. Dr. Michael Ronald Sorrell, a historian of George Mason University, aptly calls the period “Shea’s Rebellion.” [1] In April of 1967 James Shea, an associate professor of Philosophy at George Mason, emerged as the first faculty member at Mason to speak out publicly and at length on current social issues. Because of his views regarding Vietnam and the draft, his criticism of the administration at the University of Virginia and at George Mason, and his unorthodox teaching methods, Shea stirred up controversy at what was, for the most part, a quiet college campus.

By 1967, public comment on academic and social freedom was becoming commonplace at colleges and universities throughout America, although dissent against the Vietnam War was still considered radical at that time. Shea was a popular professor, largely respected by the student body. He was also very outspoken regarding his views on America’s intervention in Vietnam and was personally committed to a non-violent lifestyle. During his time at George Mason, Shea challenged students to become politically active and think critically with respect to figures of authority, be they the President of the United States or the President of the University of Virginia. Shea actively helped students organize protests, however small, on-campus and at other locations around Northern Virginia, and invited them to join him in demonstrations of his own.

James Marvin Shea, Jr., was hired in the fall of 1966 by Dean Robert C. Krug as part of an effort to fill vacancies created by both faculty resignations in May 1965 and Mason’s expansion to a four-year institution. He graduated from the University of Virginia in 1960 and took his doctorate at Cornell. He was teaching at Centenary College in Shreveport, Louisiana when he was hired on at George Mason. As Krug relates in a 2005 oral history interview, Shea traveled from Louisiana by bus as he did not own a car. Krug also recalls lending Shea a coat, as he did not own one of those, either. According to Dr. Krug, Shea was a very bright young scholar when they first met. Dr. Shea also volunteered to coach Mason’s fledgling baseball team. [2]

Shea first gained notoriety among the Mason community and in Northern Virginia by his outspokenness regarding conscription. In April 1967, he refused to accept a draft card mailed to him by the Selective Service System. Being a father to two young daughters, Shea had already been classified IIIA by the Selective Service, which meant he could not be drafted. By returning his card, he was performing an act of civil disobedience. As a result, Selective Services changed his classification to 1-A, eligible to be enlisted at a moment’s notice. Shea, who explained his personal philosophy of non-violence in a letter to the Gunston Ledger that October, declared that he was ready to go to jail if need be to avoid having to participate in the Vietnam War. He encouraged others who shared the same philosophy of non-violence to do the same. When a local politician got wind of Shea’s draft refusal, he suggested to Chancellor Thompson that Shea be removed from his teaching job. [3]

Over the next three years, Shea would be involved in several public incidents of civil disobedience. In November 1967 he reported to an induction center in Richmond as ordered by Selective Services, took the required tests and physicals, and then publically refused to step forward and take the oath. He left the center soon afterward, refusing to be inducted. [4] He would be a participant in several other episodes including draft-card burning, allegedly assisting a deserter after an automobile theft, impromptu debating with a recruiting officer in the South Building, having several arrests during demonstrations, and being interrogated by an agent of the Internal Revenue Service. Though his views and actions regarding the Vietnam War were slightly unsettling to the mainly conservative student body, faculty, and administration, they were not enough to warrant his dismissal from the college, according to Krug. Krug and Thompson did not agree with Shea’s views, but as long as the courses Shea taught were not affected by his extracurricular activities, he would be able to continue at Mason, Dean Krug maintained. [5] Dr. Shea’s teaching contract was renewed, albeit on a year-to-year basis instead of the customary three-year period.

But Dr. Shea openly rebelled against Thompson and others in the Mason and University of Virginia administrations, citing what he saw as their unwillingness to include faculty members in important policymaking processes. [6] He characterized Chancellor Thompson’s regime as repressive towards free speech and assembly, particularly with respect to new regulations instituted by the administration concerning organized protests on University of Virginia campuses in May 1968. [7] Shea aggressively pushed the boundaries of academic freedom in the classroom. For a freshmen philosophy course, Shea allegedly assigned a controversial article written by Jerry Farber, an activist and member of the UCLA faculty. The article assailed what Farber saw as a lack of freedoms offered to students at the time. The article was meant to rally the students to fight for more educational options. After Dean Robert Krug heard a student complaint that this text was substituted for Plato’s Republic, Shea became the target of increased scrutiny. [8] The administration was also concerned about Shea’s educational philosophy related to self-evaluation. Shea believed that students were the best judges of their own academic performance, therefore he encouraged each of them to submit to him their final grade based on their own self-assessment. In late 1969 he produced and distributed among the Mason community a leaflet entitled: “The Case Against Grading.” In it, he argued that the institution of grading itself was artificial and unfair. [9]

In November 1969 Shea was found guilty of being an accessory to auto theft by a Fairfax County court. Later that same day, the George Mason College Advisory Council recommended to Chancellor Thompson and University President Shannon that Dr. Shea be dismissed from his teaching duties. Still. Thompson did not act against him, and Shea remained at Mason until the fall of 1970. That November, after being convicted of a violation of federal tax law and sentenced to one year in prison, Shea abruptly left the area to avoid serving the prison term. He returned three years later to turn himself in and serve his sentence. [10]

Browse items related to Dr. James M. Shea.