The Day Care Center Controversy

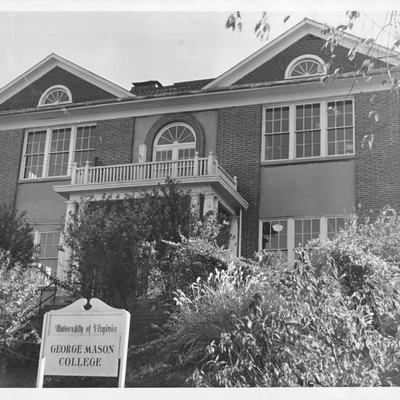

Child care facilities have been in existence since the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, such services were needed by impoverished families for which it was necessary that both parents work to provide an income. During the first half of the twentieth century, most mothers stayed at home to take care of their children. That began to change in the 1960s, as the feminist movement gained power and women began to integrate themselves into traditionally male-dominated institutions, such as the workplace and universities. This shift caused a change in the family structure as now fathers and mothers worked, leaving no one at home to take care of the children. Working parents found they needed childcare facilities. During the early 1970s, working families with a student, faculty, or staff member at George Mason agreed that a facility that would take care of their children while they worked or attended class would be helpful.

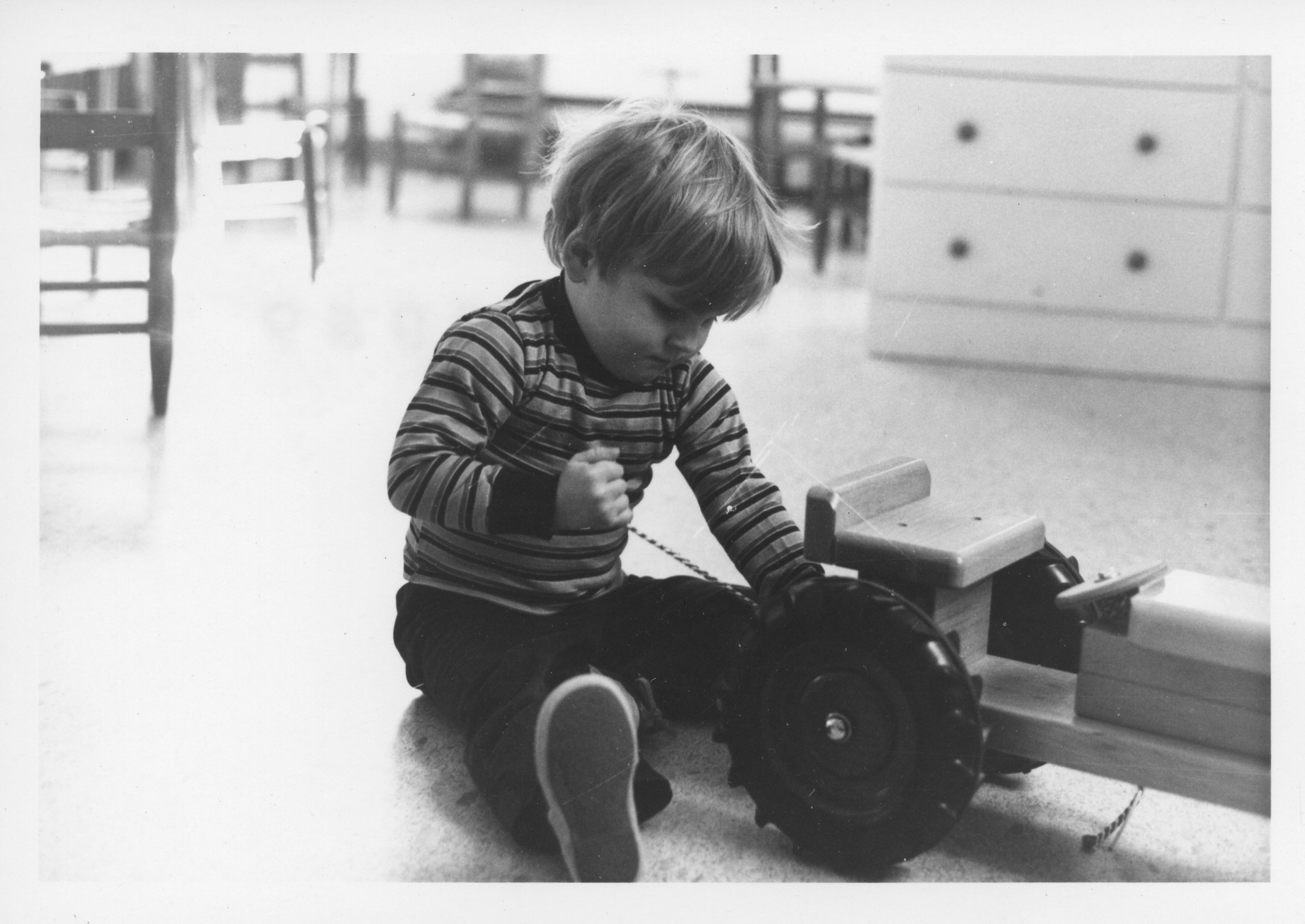

In February of 1971, Hourly Child Care Inc., the first daytime child care center on the Fairfax Campus of George Mason University, opened for business. The center, run by Reverend Roger Verley of Market Place Ministries, had been in the planning stages for one year by the time it was established along Ox Road on the western side of the Fairfax campus. [1] Rev. Verley and Dr. Ruth Green, a child care specialist who was a consultant at daycare facilities across the country, had previously operated a childcare facility in Alexandria, Virginia. That center permitted parents to leave their children to be supervised by an adult while they shopped in local malls. After conducting extensive surveys of the students and faculty at George Mason, Verley and Green determined that a similar service would thrive there as well. The daycare center was endorsed by then-college Chancellor, Lorin A. Thompson, who approved a rental agreement that would allow the school to operate on university grounds. [2]

Verley and Green conducted their not-for-profit operation out of a series of trailers and an old stone home, known as the Mallory House, on the west side of campus. This was a part of the former Oliver F. Atkins property located not far from the present location of the Field House. Atkins, a photographer for the Saturday Evening Post provided his services to George Mason from time to time. The childcare facility was particularly popular with faculty members, who often had to work around erratic class schedules. [3] However, the following year, signs of trouble emerged. In September of 1972, Lorin Thompson received an inter-office memorandum from the Dean of Students Robert Turner, conveying a variety of concerns voiced to him about the center. The subjects ranged from sanitary concerns to legal issues arising from the fact that the Hourly Child Care Center was not properly licensed by the State of Virginia. Not long after that, Broadside ran a story about the complaints lodged against the facility, popularly referred to as HCC.

HCC began a long correspondence with Virginia state officials, who now told the center that they either must apply for a license or close. Verley and Green expressed the belief that their school did not need a license, citing an obscure law that stated that a child care center affiliated with a university did not need to be licensed. President Thompson, while still a strong advocate of the center, was firm in his stance that HCC was a private entity not affiliated with the university. HCC’s only connection with George Mason University was that it rented space on the Fairfax Campus. HCC finally agreed to apply for a license, but disagreed with several stipulations, such as the requirement that children staying past noon must be served a hot lunch. Verley and Green argued that such rules hurt the center’s role as a place where parents could leave and pick up their children on an irregular schedule. In August of 1973 HCC learned that they would be issued a license by the Department of Welfare and Institutions of the Commonwealth of Virginia. This license authorized HCC to operate the child care center for one year.

Earlier that summer, however, Dr. Vergil Dykstra had been named the new President of George Mason University. Dykstra did not think that it was appropriate that a child care center should operate on university grounds. [4] In July of 1973, just before HCC was scheduled to receive its license, Dykstra sent a letter to HCC expressing his intent to immediately terminate the child care center’s rental agreement. [5] Verley was able to convince Dykstra to negotiate a year-long extension of the rental agreement since the center was now licensed. HCC would eventually move to a nearby church in 1975.

The Student Government (SG), troubled by the allegations brought up by Broadside, weighed in on the controversy. It formed its own child care center on campus. The George Mason University Student Government Child Care Center opened on campus in time for the Fall 1973 semester. [6] Though some money was allocated to the center by the SG, the group helped choose its board of directors, and the center was named for the SG, it did not claim to be directly affiliated with the SG. The Student Government Child Care Center proved to be a popular solution to the childcare problem on campus, though it eventually closed.

In 1992, the Child Development Center opened in Patriot Village, a series of trailers located not far from the present location of the Mason Inn. The facility, which only accepts the children of Mason faculty, staff, and students, has been widely praised by its patrons. In 2007, the Child Development Center moved to a new building next to the water tower on University Drive where it is presently located.

Browse items related to the childcare center controversy.

[1] Roger Verley to Lorin Thompson, January 5, 1970, Office of the President Records 8.14

[2] Letter from Lorin Thompson to Roger Verley, February 9, 1971, Office of the President Records 8.14

[3] Letter from Roger Verley to Lorin Thompson, March 14, 1972, Office of the President Records 8.14

[4] Vergil Dykstra Oral History, 2009

[5] Letter from Vergil Dykstra to Roger Verley, July 17, 1973, Office of the President Records 9.2

[6] Broadside, September 4, 1973